So, back in 1967, what was the big concern about the Tsetse Fly, and why were so many financial and logistical resources expended to try and control this little pesky critter? The reality then, and now, is that the Tsetse Fly is one of the roots of Africa’s poverty. No other region of the world suffers the same animal health problems as the tsetse fly imposes on Africa.

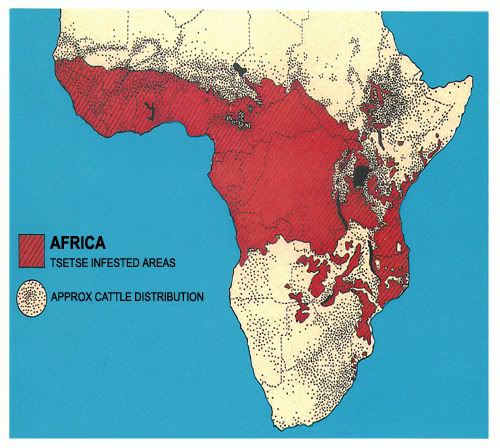

Sleeping Sickness and Nagana are diseases transmitted by the Tsetse Fly. According to the deputy director-general of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) " It is no accident that the concentration of much of the world's most acute poverty is in regions of sub-Saharan Africa infested with tsetse." Some experts say that the Trypanosomiasis pathogen helps create African "green deserts" -- 10 million square kilometers of otherwise lush and fertile land that is not in production because of the tsetse fly carrier. This includes land in 32 of the world's poorest countries.

The presence of the disease Nagana, which is deadly to most cattle, prevents rural villagers from using cattle or horses as draft animals which could improve their agricultural productivity by 25 to 45%. "Allowing more African farmers to own livestock would have a profound impact on hunger and poverty in the continent, but that cannot be achieved without the elimination of the tsetse fly." Native breeds of cattle (Zebu), which will be familiar to those who have traveled to East Africa on safari, are only somewhat resistant to Nagana.

Cross-bred cattle whose milk production is NINE times the native breeds, cannot survive in tsetse fly areas.Ironically, it is the presence of the tsetse fly (and the diseases that it carries) across great tracts of Africa that protected land from over-development during the last century of European settlement and expansion. This enabled both the colonial rulers and subsequently the governments of independent states to develop their wildlife resources by establishing National Parks and Wildlife Management areas. The Game Reserves of Kenya, Tanzania, South Africa, Zimbabwe and Botswana almost certainly would not have been set aside for the conservation of wildlife had they been of economic value for ranching and crop production.

The tsetse fly thrives in an environment where there are large populations of wildlife providing an unlimited and year-round supply of essential mammalian blood on which they must feed to survive and reproduce.

Nearly 45,000 cases of sleeping sickness (or Trypanosoma as the pathogen is called) were reported in Africa in 1999. However, only three to four million of the over 60 million people at risk are being screened and the number of cases may be as high as 500,000, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports. In the absence of effective screening most people with sleeping sickness die before they can ever be diagnosed. Early diagnosis offers a relatively high chance of cure. Back in the 1960’s and before, the extent of the disease was worse.

The disease causes an acute infection that emerges after a few weeks and which can infect a person for months, or years, without symptoms, while parasites multiply in the bloodstream and lymphatic system. When they cross the blood-brain barrier and invade the central nervous system, there are neurological changes that are often irreversible, and which require a strict and complex regimen of treatment.

The trypanosome is carried in the blood of most African antelope species, as well as other vertebrates such as elephant, cape buffalo, warthogs and bush pigs; all of which are immune to its effects. Horses, cattle, dogs, and other domesticated animals will die when exposed to the bite of the tsetse fly if not maintained on a regular course of prophylactic drugs. The trypanosomes in many areas have become resistant to these drugs.

There is hope for the future. In 1996, the IAEA assisted in the development of a technique of sterilizing the male tsetse fly using radiation. Large numbers of sterilized males are released into the countryside. The female fly only mates once in her lifetime, and so the larvae that she lays once every week to ten days does not live. In a trial conducted on the isolated island of Zanzibar, off of the East African coast, the tsetse fly population was eradicated and farming productivity rose dramatically in the years following this trail. The use of this technique on the African mainland holds hope for similar results, but campaigns would require large financial and human resources, and close cooperation across borders and government jurisdictions to achieve long-term success.

When I became a Field Entomologist, or Glossinologist, in the “Tsetse and Trypanosomiasis Control Branch” of the Department of Veterinary Services for the Government of Rhodesia in 1967, that progressive country was achieving considerable success in clearing large areas of the tsetse fly. The extensive, and costly, operations had the vital purpose of opening up new land for settlement to meet a rapidly growing demand for productive farm land for a fast-growing native population. In many areas of the country land was very fertile, but cattle and other domestic livestock or draft animals could not survive.

In my next blog I will describe the basics of a Tsetse Control operation 44 years ago.

|

| Red marks the extent of Tsetse Fly infestation - as of 1999. |

No comments:

Post a Comment

Your comments are appreciated!